Por Luiz Cláudio S Ferreira (DecoStop Nr 61)

Since the 19th century, diving with rebreathers, devices capable of recycling the air exhaled by the diver, has evolved from experimental devices to advanced diving systems in both military and civilian environments. The first documented attempt to use a closed-circuit device occurred in 1878, when British engineer Henry Fleuss invented a rebreather that used pure oxygen and a soda lime system to absorb exhaled carbon dioxide. Fleuss tested the equipment in underwater repair operations and, although his device had a limited lifespan and was risky, it laid the foundation for a new type of diving technology.

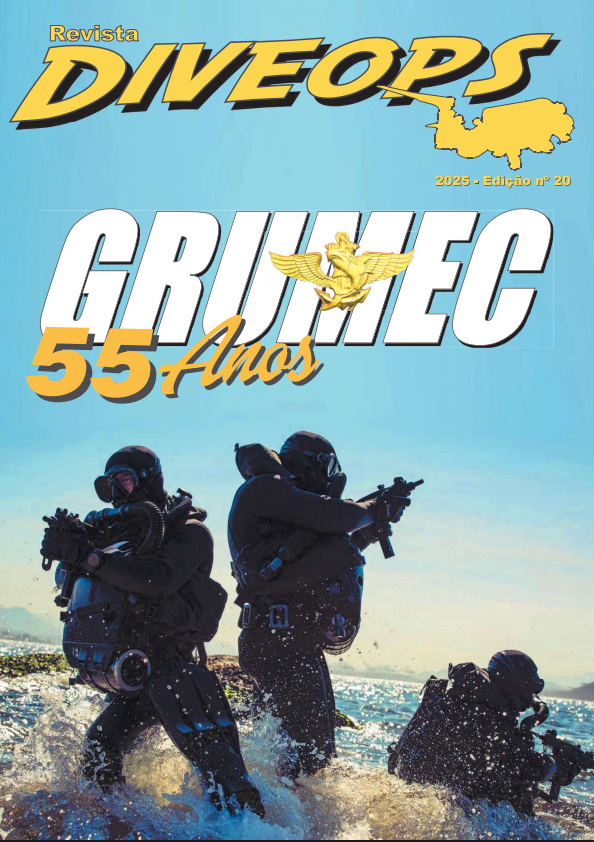

During World War II, military forces, especially the Italian Navy, adopted the use of rebreathers in war missions, where the absence of bubbles was crucial to maintaining stealth. And throughout the 20th century, scientists and engineers such as Christian Lambertsen contributed to the improvement of this technology. Lambertsen, who is often credited with inventing the modern rebreather, developed the Lambertsen Amphibious Respiratory Unit (LARU) [Fig. 1] for the United States Navy, which played an important role in special operations. Soon after, navies such as the United Kingdom and Israel also invested in research and developed equipment of a primarily military nature

Fig. 1 – Lambertsen Amphibious Respiratory Unit (LARU) during World War II

In the 1960s and 1970s, with the development of more efficient valves and the use of gas mixtures, these marvelous machines began to be used in scientific and technical diving as well. In other words, this advancement made civilian use possible, especially in cave and shipwreck exploration. Today, rebreathers continue to evolve, becoming essential tools for both military diving by armies around the world, including the Brazilian Armed Forces (including the Brazilian Navy and the Brazilian Army), and for civilian technical and recreational diving.

The different gas recovery systems in modern rebreathers: CCR and SCR

Rebreathers are essentially self-contained breathing devices that operate by recycling the air exhaled by the diver, removing carbon dioxide (CO₂) and adjusting the oxygen concentration (O₂) as needed to maintain a breathable mixture. This process occurs cyclically, using components known as “counter-lungs” – flexible bags that store respiratory gas between inhalations and exhalations. When exhaling, the gas passes through a soda lime chemical filter (scrubber) that removes the CO₂ before being recirculated, while sensors monitor the O₂ concentration, injecting pure oxygen as needed.

There are two main types of rebreathers: closed circuit (CCR) and semi-open circuit (SCR). In CCR, all exhaled gas is recirculated after the CO₂ is removed, with oxygen dosing carried out automatically or manually to maintain a precise breathing mixture. This continuous cycle allows the diver to breathe without the emission of bubbles, making it ideal for deep and long dives, where discretion and gas economy are essential.

The SCR, on the other hand, expels part of the exhaled gas and adds fresh gas with each cycle, maintaining a safe and constant mixture. This configuration, although less efficient than the CCR in terms of gas economy, is simpler and more accessible, and is ideal for medium-depth dives, where a constant flow of gas increases safety and complete elimination of bubbles is not an essential requirement.

The application determines the machine system: Electronic vs. Mechanical

As is well known, rebreathers play an essential role in both military operations and civilian explorations. However, the specific choice of equipment has been guided by the nature of the activity, indicating that the main dividing line between civilian and military applications is not only between CCR or SCR systems, but between electronic and mechanical machines.

In the civilian field, electronic rebreathers dominate in recreational and technical applications that require depth, precision and comfort. These devices use oxygen sensor systems, solenoids and dive computers to monitor and automatically adjust the oxygen concentration [Fig. 2], ensuring an ideal breathing mixture for the diver at each depth. The precision of these systems makes them intuitive to use, reducing the diver’s operational load and allowing greater control of breathing. Studies by the Divers Alert Network (DAN) reinforce that electronic rebreathers are ideal for civilian jobs, providing automatic and safe control of the breathing mixture, thus reducing complexity and physical effort.

Fig. 2 – Sidewinder 2 rebreather electronic head with three oxygen sensors and Shearwater Petrel computer

In contrast, mechanical rebreathers, such as the Dräger LAR V and Aqualung’s FROGS “Full Range Oxygen Gas System” [Fig. 3], are preferred in military operations, where robustness and simplicity are paramount. Unlike electronic models, these systems do not require sensors and automatic mechanisms, operating essentially mechanically and, importantly, immune to the possibility of electromagnetic interference. Through manually controlled valves and levers, the diver adjusts the oxygen concentration independently, eliminating the need for electronic components that could fail under extreme conditions or in electromagnetic interference scenarios. This simplicity of operation is strategic for military forces in hostile environments, as it reduces the risk of technical failures and allows the equipment to function reliably in unpredictable scenarios.

Fig. 3 – FROGS mechanical rebreather

In fact, there is no doubt that the choice between electronic and mechanical rebreathers ends up being defined by the environment and purpose of the activity.

Comparison between military and civilian use

The use of rebreathers in military and civilian contexts reflects specific needs and challenges, shaped by operational, environmental and physical factors.

In the civilian environment, rebreathers maximize safety and autonomy in diving, allowing precise control and comfort, minimizing the physical demands on the diver, in addition to ensuring silent operation, essential for technical divers, researchers, underwater photographers and marine biologists, who seek to observe sensitive ecosystems without causing disturbances, as well as extreme cavers, who want to avoid sediment precipitation due to the collision of bubbles with the ceiling of unstable environments, the silt. Studies such as those published in the Journal of Diving and Hyperbaric Medicine confirm that the use of rebreathers in civilian explorations increases safety and allows divers to reach greater depths with less gas consumption, optimizing the duration and quality of the dive, whether for recreational or commercial purposes. In contrast, rebreathers are used in the military context for infiltration, approach, reconnaissance and rescue operations in hostile environments, search and refloat of personnel and material, inspections and minor repairs of vessels, reconnaissance, sabotage, direct combat actions, extraction of personnel or material, marking of banks, launching obstacles, opening breaches and underwater demolitions [Fig. 4]. Most of the time, these activities are carried out using combined means of displacement, such as the use of boats and parachute launches, and always accompanied by the factor of “imminent risk of contact with enemy troops”. Naturally, the absence of bubbles, an essential characteristic of these machines, allows a high level of discretion, indispensable for combat missions.

Fig. 4 – CIOpEsp, credit Cap Dimas

Although both sectors demand precision and safety for the use of rebreathers, it can be said that the military and civilian contexts differ essentially in the minimum level of associated demands on the part of the operator. Military employment requires more resilience, job training associated with other skills and physical robustness to withstand the demands characteristic of military operations; the civilian context prioritizes ease of operation and safety, even when carrying out complex commercial operations.

Military training and civilian preparation for the use of rebreathers

Training for the use of rebreathers in the military context is rigorous and meticulously planned for demands of high personal risk. At the Special Operations Training Center (CI Op Esp) of the Brazilian Army, located in the city of Niterói, for example, when taking the Oxygen Diving Internship (EMOX) with the FROGS mechanical rebreather, Brazilian Special Forces soldiers are repeatedly subjected to a series of exercises that simulate extreme scenarios. These include long-distance swimming, deep-water breathing resistance and underwater rescue simulations, with the integration of weapons, long-distance underwater navigation instruments [Fig. 5] and other combat equipment, preparing soldiers for missions in different types of scenarios and in prolonged situations.

Fig. 5 – CIOpEsp, credit Cap Dimas

In the Brazilian Navy, the Expedito Curso de Gulho Autônomo com Circulo Fechado (C Exp MAut Gás) follows a similar approach, training military personnel to use rebreathers in complex maritime missions. This technical course prepares divers to face adverse conditions, covering all aspects of FROGS operation and ensuring that divers can operate accurately even in low visibility and high pressure scenarios.

In addition to technical skills, military training places a strong emphasis on psychomotor [Fig. 6] and emotional preparation. Military divers must be able to handle both breathing and combat equipment with skill and precision, especially in conditions of limited visibility. From an emotional perspective, stress management is essential, as the ability to make quick decisions and remain calm under pressure is crucial in combat operations. Elite forces like the Navy SEALs, for example, develop specific breathing control and emotional resilience techniques, including exercises like meditation and high-stress simulations to prepare divers for the unique challenges of underwater combat.

Fig. 6 – US Army, credit Sgt. Dominique Cox

In the civilian sector, training for the use of rebreathers is similarly structured, but with a focus on the safety and efficiency of the equipment. Specialized diving centers offer courses that cover the configuration, monitoring and operation of the machines in technical scenarios such as cave exploration and shipwreck exploration. These courses include simulations of emergency situations and detailed instructions on oxygen consumption management and rescue procedures. Although civilian training does not reach the same levels of physical and psychological intensity required in the military environment, continuous practice and technical knowledge are equally essential to ensure safety in difficult-to-access environments and in prolonged diving situations.

Therefore, military training for rebreathers is marked by an approach that integrates technical skills, physical preparation and emotional control for operations in extreme environments, while civilian training focuses on technical mastery, safety and, eventually, training to perform commercial tasks.

Psychological impact and stress in military and civilian contexts

The psychological impact and stress management of using rebreathers vary substantially between military and civilian employment, due to the specific demands and requirements of each environment.

In the civilian sector, rebreather use, although involving emotional control and emergency response, occurs in relatively controlled and predictable scenarios. Civilian divers face intense challenges in technical explorations, such as deep cave diving or remote wreck diving, but their focus is on self-sufficiency and managing technical problems for the sake of personal safety. These situations require the diver to remain calm and resolve potential emergencies, but the pressure is essentially internal and self-driven. For many civilian divers, rebreather use also represents an experience of self-satisfaction, associated with a sense of achievement in overcoming limits previously unattainable with conventional equipment.

In contrast, military divers face a higher level of psychological and physical stress, shaped by the operational demands of combat. Studies such as that by Michael Tipton and Frank Golden, published by the Institute of Naval Medicine in 2009, highlight that the challenges faced by military divers go beyond technical requirements, involving extreme conditions of physical endurance and sensory deprivation [Fig. 7]. In underwater combat operations, where absolute silence and precision of movements are critical to the safety of the team, detection by the enemy is a constant threat, intensifying the emotional burden of the activity. Military training, as previously mentioned, needs to be focused on emotional resilience and psychological control, addressing not only technical skills, but also the management of extreme stress.

Fig 7 – US Army, credit Robert Lindee

In addition to conventional training, military divers undergo simulations that include combat situations and troubleshooting in unexpected conditions, preparing them for dynamic and unpredictable scenarios. These trainings teach operators to maintain concentration under sensory deprivation and to make quick and accurate decisions, even in adverse conditions where any mistake can have fatal consequences. According to Tipton and Golden, training in emotional resilience and breathing control techniques is essential for military divers to manage the stress underlying missions and maintain operational efficiency. Publications such as those in the Journal of Special Operations Medicine emphasize that this type of specific training is crucial to the safety and performance of underwater military operations, helping operators to remain alert and operational, even in moments of extreme pressure.

The psychological demands between the two contexts reflect the different purposes and realities of each sector. Thus, the same equipment, although technologically similar, challenges and shapes the user in different ways, requiring a level of emotional preparation and resilience that is unmatched in the military environment.

Conclusion

Rebreathers represent a fascinating point of convergence between military operations and civilian exploration. In the military field, they are an essential strategic tool, enabling operations to be carried out with discretion and efficiency, especially in conditions where silence and invisibility are crucial. The robust simplicity of mechanical models and the high level of military training ensure that these devices meet the specific needs of Special Forces around the world.

In the civilian field, rebreathers have opened up new possibilities for exploration. The development of easy-to-use electronic rebreathers has democratized access to previously unexplored depths, allowing civilian divers to explore wrecks, caves and deep-sea ecosystems safely and efficiently. This popularization reflects a significant advance in diving technology and in the understanding of the limitations and possibilities of the human body in extreme underwater environments.

Whether for military missions or civilian exploration, the rebreather symbolizes the intersection between technological capability and human potential, expanding frontiers and allowing new generations of divers to reach depths that were previously exclusive to fish.

Acknowledgements

My thanks to the Commander of the Special Operations Training Center (CIOpEsp) [Fig. 8], Col. Inf QEMA Gian Dermário da Silva, for the generous opportunity granted by opening the doors of the Army Diving School, under the tutelage of his Military Organization (OM). This concession allowed for the deepening of various aspects of military diving with rebreather, while maintaining the necessary reserve of strategic knowledge and doctrine of restricted military use. The experience provided, ranging from the preparation of personnel to the handling of the FROGS machine, was of inestimable value and significantly enriched the understanding of the demands and challenges of this unique area.

Fig 8 – credit Colonel R1 Luiz Cláudio (author)

I would also like to highlight the importance of the mission of this respectable Military Organization of the Brazilian Army, the most noble combat reserve available to the Force Command, which combines technical excellence, meticulous preparation and an unrestricted commitment to the defense of the nation. The figure of the Special Forces soldier, whose selflessness and courage stand as a unique example of dedication and professionalism, is a source of inspiration and immense respect for all of us.

I reiterate my gratitude for the welcome, for sharing knowledge and for the nobility demonstrated in all interactions. May the spirit of excellence that permeates that Unit continue to be a reference for all who share the commitment to the security and future of our country. I would like to express my gratitude to Infantry Captain Dimas Corrêa Toscano de Oliveira and Infantry Sergeant Raimundo Felinto de Melo, coordinators of the Army Diving School and members of the CIOpEsp training team, who were assigned to guide me through the select universe of oxygen divers in Brazil’s Special Operations and did so with extreme courtesy and a sense of commitment.

FORÇA!!!

Sources of Reference

⦁ Fleuss, H. (1878). “Submarine Operations and Devices.”

⦁ Lambertsen, C. J. (1940s). “Development of Closed Circuit Oxygen Rebreathers.” Naval Research Laboratory.

⦁ Journal of Diving and Hyperbaric Medicine: Divers’ Rebreather Usage and Technological Advances.

⦁ Journal of Special Operations Medicine: Psychological and Physical Training for Military Divers.

⦁ Ambient Pressure Diving (fabricante): “Inspiration Closed Circuit Rebreathers.”

⦁ US Navy (2006). “19”. US Navy Diving Manual, 6th revision. United States: US Naval Sea Systems Command. p. 13. Retrieved 2008-06-15.

⦁ Perry, Tony (2013-11-03). “John Spence dies at 95; Navy diver and pioneering WWII ‘frogman'”. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2013-11-27.

⦁ ARENT, Carlos Eduardo Horta. Mergulhadores de Combate comemoram 40 anos no Brasil. O Periscópio, Rio de Janeiro, ano XLVIII, nº 66, p.8. 2013.

⦁ MACIEL, Luiz Eduardo Cetrim. Preparation of the crew and their families for Deployment commissions. O Pericópio, Rio de Janeiro, year XLVIII, nº 66, p.23. 2013.

⦁ Pinheiro, Álvaro de Sousa (agosto de 2012). «Knowing your partner: the evolution of Brazilian special operations forces» (PDF). Joint Special Operations University. JSOU Report (em inglês): 12-7. Consultado em 17 de janeiro de 2024

⦁ Bonds, Ray (2003). Illustrated Directory of Special Forces (em inglês). Saint Paul, Minnesota: Voyageur Press. p. 19. ISBN 978-0760314197. OCLC 51555045

⦁ Neville, Leigh (2019). The Elite: The A–Z of Modern Special Operations Forces (em inglês). Londres: Osprey Publishing. p. 68. ISBN 978-1472824318. OCLC

Author

Luiz Cláudio da Silva Ferreira

CMAS Instructor # M3/10/00001

PADI Tec TRIMIX/DSAT Instructor # 297219

DAN Instructor #14249

#007.615.457-27