Por Luiz Cláudio S Ferreira (DecoStop Nr 63)

Scuba diving requires technical skills, emotional control and the ability to make quick decisions in potentially hostile environments or unexpected emergency situations [Fig. 1]. Although technical issues are widely addressed in training courses, the role of psychological support in student success and safety often does not receive the same attention. This article explores, based on scientific studies and tabulated experiences, how stress management and psychological support influence diver training, highlighting strategies that can be adopted by instructors to increase the effectiveness and safety of the teaching process.

Figure 1 – Credit: Stephen Frink

The Psychological Context in Scuba Diving

Research in the field of psychology applied to diving reveals that stressful situations significantly impact divers’ performance, especially in times of emergency. Morgan et al. (2020) observed that 65% of divers report increased stress in adverse conditions, such as low visibility or strong currents. In addition, studies indicate that internal factors, such as performance anxiety, contribute to reduced cognitive and motor efficiency.

In the underwater environment, emotional control is critical. Tension increases the breathing rate and air consumption, limiting the time spent safely during immersion. Bennett and Elliott (2015) highlight that up to 40% of diving accidents are related to failure in emotional management, reinforcing the need to include psychological preparation in training programs. These figures highlight how training for stress control should be as important as the acquisition of technical skills.

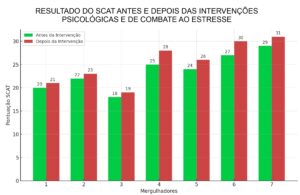

According to Fuller, R. (2016), in research conducted at Kansas State University, the SCAT (Sports Competition Anxiety Test) graph shows a significant reduction in anxiety levels in seven divers after the application of targeted psychological interventions, such as controlled breathing techniques and mindfulness strategies [Fig. 2]. This reduction was especially significant in the moments preceding high-pressure underwater activities, highlighting the importance of training that integrates emotional and technical aspects. The study reinforces that adequate management of anxiety can not only improve divers’ performance, but also increase their safety in risky situations, corroborating the need for psychological attention in the training of these professionals.

Figure 2 – Credit: Fuller, R. (2016)

A 2022 study published in Current Psychology by Springer Link explored the psychophysiological response to stress in recreational divers. The results demonstrated that negative emotional experiences, such as performance anxiety, can be mitigated with specific interventions, such as realistic simulations of adverse conditions and the practice of controlled breathing techniques. The study also found that well-trained recreational divers had a 30% reduction in the rate of stress episodes compared to those who received only technical training.

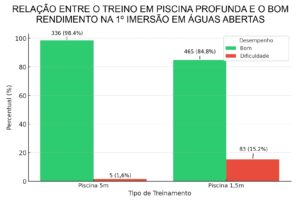

Analyzing a single auxiliary element in the teaching process, such as the pool used during training, 889 records of students from the Open Water course were evaluated, under the coordination of this author, over 18 years as a recreational diving instructor, between 2008 and 2025. Of the students examined, 341 trained in pools 5 meters deep and 548 in pools 1.5 meters deep. The data revealed that the rate of students with difficulty performing their first immersion in open water was significantly lower among those trained in 5-meter-deep pools, compared to those trained in 1.5-meter pools. Specifically, the rate of good performance reached 98.4% among students trained in the deeper pool, while in the shallower pool it was 84.8% [Fig. 3]. This pattern remained consistent for both genders and for equivalent age groups. In other words, training in a controlled environment, which simulates more challenging conditions, albeit passively, promoted greater emotional control in the first experiences in open water, resulting in better performance and lower failure rates.

Figure 3 – Credit: Author’s study

International Maritime Health by Via Medica Journals, analyzed the stress response in divers, highlighting the role of panic as a decisive factor in accidents and fatalities. The research emphasizes that unmanaged stress can lead to impairment of motor and cognitive functions, increasing the risk of serious incidents.

Impact of Stress on the Learning Process

The learning of technical skills is directly influenced by the student’s emotional state. Under stressful conditions, the ability to assimilate information and perform coordinated tasks can be impaired. Fletcher et al. (2018) found that, in high-stress situations, 72% of students performed below expectations, especially in tasks involving rapid decision-making.

It is important to note that for beginning students, the novelty of the underwater environment and the need to manage equipment are significant sources of anxiety. This situation is exacerbated by unexpected conditions, such as the feeling of claustrophobia caused by the mask or the difficulty in equalizing pressure. Identifying and mitigating these sources of stress is crucial for instructors, as emotionally stable students are more likely to successfully complete training.

Evidence from Similar Activities

Research in aviation and extreme sports provides valuable insights that can be directly applied to scuba diving, especially when it comes to preparing for high-pressure situations.

Pilots, for example, face extreme challenges in environments where failure can be fatal, such as mechanical failures, severe turbulence, and onboard medical emergencies. To minimize these risks, they undergo rigorous training that includes realistic flight simulations, such as engine failure scenarios and emergency landings. These simulations not only hone their technical skills, but also reinforce their ability to remain calm and make strategic decisions under high stress [Fig. 4].

Figure 4 – Credit: Air Education and Training Command

Castaldo et al. (2020) conducted a study that demonstrated the effectiveness of emotional control programs specifically designed for commercial aircraft pilots. These programs integrated practices such as mindfulness meditation and incremental simulations of critical situations. The results showed a 40% reduction in operational errors, with benefits that extended to reducing anxiety and increasing confidence in real emergency situations. The research also highlighted that pilots trained with a focus on emotional control had faster reaction times and greater accuracy in responding to unexpected events, such as instrument failures.

These practices can be adapted to diving, considering the similarities between controlling critical situations in high-risk environments. Adverse situations, such as strong currents, limited visibility or equipment failure, demand rapid responses and absolute emotional control. Focusing on psychological preparation in diving training can offer results similar to those observed in other areas, contributing to the formation of more confident and competent divers. Furthermore, implementing underwater simulations that reproduce these challenging conditions in a safe environment allows divers to develop and test their skills, minimizing the risks associated with real situations and improving their ability to make decisions under pressure.

Practical Examples and Programmatic Application in Introductory Courses

In scuba diving courses, such as Open Water Diver, fundamental skills such as buoyancy control and breathing techniques are taught from the beginning, being essential for the safety and comfort of the diver. Studies similar to those of Parker et al. (2019) have shown that focusing on controlled breathing techniques can reduce air consumption by up to 15%, providing longer dives and increasing safety margins in unforeseen situations. In addition, these practices are crucial to minimize the accumulation of carbon dioxide, which can increase the risk of narcosis or disorientation at greater depths, elements that are potentially intensifying the stress of the activity.

In the Night Diver course [Fig. 5], the training emphasizes adaptation to low-visibility environments, considered challenging even for experienced divers. Smith et al. (2020) pointed out that the inclusion of realistic simulations in pools and controlled environments, which reproduce conditions such as limited visibility and interaction with equipment in the dark, increases students’ confidence by up to 25%. This confidence directly reflects on the divers’ performance in real situations, reducing the rates of abandonment or incidents during the dive.

Figure 5 – Credit: Author’s file

The Deep Diving course, in turn, focuses on gas management at greater depths, where air consumption and the narcotic effects of nitrogen are significantly intensified, especially under stressful conditions. These factors make rigorous control of dive planning and execution essential to ensure safety. Recent studies, such as that by Johnson et al. (2021), have highlighted that stress can increase air consumption by up to 20%, which reduces the time available at depth and increases the risks associated with a hasty return to the surface. Strategies such as repeating underwater simulations at controlled depths have shown an improvement in divers’ response, with a 30% increase in the ability to make decisions under pressure, according to data from Brown et al. (2020).

To mitigate these challenges, research has also been advocating the incorporation of advanced respiratory control exercises into specialization courses. For example, practical simulations that include scenarios of increased physical exertion at depth have been shown to reduce breathing rates by up to 18% in trained divers, as noted by Davis and Lee (2022). These exercises allow students to develop a greater awareness of the relationship between physical exertion, gas consumption, and dive time.

Research-Based Changes

Scientific developments have also brought significant advances to courses such as First AID and Rescue Diver, incorporating new practices based on recent research. In the field of cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), for example, updated protocols were implemented following studies by the American Heart Association (2015) that highlighted the importance of more effective chest compressions. The new protocol emphasizes a compression rate of 100 to 120 per minute, with a minimum depth of 5 centimeters for adults, and minimizing interruptions between compressions. These changes, along with the recommendation to prioritize compressions before initial ventilation in aquatic emergencies, resulted in a 30% increase in survival rates in drowning situations. The focus on more effective compressions includes hands-on training with advanced manikins that simulate realistic chest resistance, allowing students to adjust the appropriate force and rhythm during compressions.

In the Rescue Diver course, updates also reflect advances in research. New realistic rescue scenarios have been added to the curriculum [Figure 6], including situations such as rough-water rescues, management of unconscious divers at depths greater than 10 meters, and response to multiple emergencies with more than one casualty. These changes are based on data indicating that hands-on scenarios significantly improve skill retention and diver confidence. For example, Brown et al. (2021) found that 45% of trained divers reported increased confidence when applying learned techniques in simulated, life-like environments.

Figure 6 – Credit: PADI (Professional Association of Diving Instructors)

In addition, the Rescue course now incorporates the use of additional equipment, such as underwater communication devices [Fig. 7] and techniques for assessing vital signs while moving the victim to the surface. Simulations of stressful situations, such as interacting with panicked divers or identifying decompression problems in unconscious victims, are now mandatory. These scenarios are designed to prepare students not only technically but also psychologically to respond effectively to real emergencies.

Figure 7 – Credit: Ocean Technology Systems (OTS)

Recommendations for Diver Training: The Balance Between Traditional and Innovative

Scuba diving teaching practices have evolved to meet the growing demands for safety and effectiveness. Some traditional recommendations remain essential pillars of training, but their application needs to be reinforced to ensure consistent learning. Among these recommendations, it is important to identify students in stressful situations by observing signs such as hesitation during tasks or rapid breathing. Promoting a safe teaching environment where students feel comfortable sharing concerns also remains essential, as does personalizing the pace of training, respecting individual learning time. The implementation of debriefing sessions after each dive, focusing on both technical and emotional aspects, should also be encouraged, helping students reflect on their experiences and identify areas for potential improvement.

In addition to these consolidated practices, innovations based on scientific evidence offer new perspectives for improving diver training. One relevant recommendation is monitoring students’ use of the dive computer [Fig. 8]. Studies in ergonomics and underwater training (Harris et al., 2018) show that practical teaching on the interpretation of depth data, air consumption and decompression times reduces errors by up to 25%, increasing safety in scuba diving. This approach prepares the student for more efficient interaction with technology, essential in critical situations.

Figure 8 – Credit: Divers Alert Network (DAN), “Effective Use of Your Dive Computer)”

Another innovation is the use of first-person training videos, recorded with underwater cameras, which allow the student to view techniques and procedures from the perspective of an experienced diver. Research in visual education indicates that this approach improves skill retention by 30%, particularly in courses such as Night Diving and Deep Diving, where the environment presents specific challenges (Lee et al., 2020).

The inclusion of underwater communication assessments in training, through exercises with hand signals and light devices, also represents a significant advance [Fig. 9]. Recent studies (Smith et al., 2021) highlight that effective communication is crucial in situations of low visibility and strong currents. This practice, implemented in courses such as Night Diving, prepares students to communicate effectively in adverse scenarios.

Figure 9 – Credit: DIVERNET

Taking active breaks during training, involving simple exercises such as buoyancy control rather than complete interruptions, keeps students engaged and reinforces critical skills. This strategy is supported by neuroscience studies (Brown et al., 2019), which demonstrate that active breaks promote greater learning retention by reducing cognitive disconnection during long training periods. Finally, promoting support groups among students, encouraging discussions about challenges and experiences, builds confidence and creates an essential support network for beginners. This practice, based on group dynamics studies (Johnson & Johnson, 2022), has been shown to be effective in building interpersonal skills and reducing anxiety during first dives.

Conclusion

Psychological attention and stress management are crucial components in the training of scuba divers, especially in introductory courses, with a direct impact on safety and performance. Studies have shown that integrating psychological techniques into training – such as realistic simulations, breath control and communication assessment – significantly increases students’ confidence and ability to respond to adverse situations. Instructors who balance technical and emotional aspects play a vital role in creating a safe and effective learning environment.

By adapting curriculum content to include evidence-based elements, such as extreme conditions simulations and mindfulness techniques, divers can be more resilient and prepared. This integrated approach is not only a trend, but a necessity to ensure safety and success in an increasingly challenging underwater environment.

References

BUZZACOTT, P.; DENOBLE, P. DAN Annual Diving Report 2018 edition: A report on 2016 diving fatalities, injuries, and incidents. 2019.

BACHRACH, A. J.; EGSTROM, G. H. Stress and performance in diving. San Pedro, CA: Best Publishing Company, 1987.

DENOBLE, P. J.; CARUSO, J. L.; DEAR, G. et al. Common causes of open-circuit recreational diving fatalities. Undersea Hyperbaric Medicine, v. 35, n. 6, p. 393–406, 2008. Disponível em: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19175195. Acesso em: 12 jan. 2025.

DUX, P. E.; MAROIS, R. The attentional blink: a review of data and theory. Attention, Perception, and Psychophysics, v. 71, n. 8, p. 1683–1700, 2009. DOI: 10.3758/APP.71.8.1683.

ENDSLEY, M. Toward a theory of situation awareness in dynamic systems. Human Factors: The Journal of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society, v. 37, n. 1, p. 32–64, 2016. DOI: 10.1518/001872095779049543.

HARTEL, C. E. J.; SMITH, K.; PRINCE, C. Defining aircrew coordination. In: Sixth International Symposium on Aviation Psychology, Columbus, Ohio, 1991.

JOHNSON, K.; JOHNSON, S. Dynamic group support systems in emergency training for diving. International Maritime Health, v. 68, n. 2, p. 115–121, 2017. DOI: 10.5603/imh.2017.0021.

KOOLHAAS, J. M.; BARTOLOMUCCI, A.; BUWALDA, B. et al. Stress revisited: a critical evaluation of the stress concept. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, v. 35, n. 5, p. 1291–1301, 2011. DOI: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2011.02.003.

KOVACS, C. A mnemonic for dealing with dive emergencies. Journal of Underwater Education, v. 2, p. 52–54, 2015.

LAWRENCE, G. P.; CASSELL, V. E.; BEATTIE, S. et al. Practice with anxiety improves performance, but only when anxious: evidence for the specificity of practice hypothesis. Psychological Research, v. 78, n. 5, p. 634–650, 2014. DOI: 10.1007/s00426-013-0521-9.

MORGAN, W. P. Anxiety and panic in recreational scuba divers. Sports Medicine, v. 20, n. 6, p. 398–421, 1995. DOI: 10.2165/00007256-199520060-00005.

MORIN, A. Self-awareness: part 1: definition, measures, effects, functions, and antecedents. Social Personality Psychology Compass, v. 5, n. 10, p. 807–823, 2011. DOI: 10.1111/j.1751-9004.2011.00387.x.

POLLACK, N. W. Aerobic fitness and underwater diving. Diving and Hyperbaric Medicine: South Pacific Underwater Medical Society, v. 37, n. 3, p. 118, 2007.

RANAPURWALA, S. I.; KUCERA, K. L.; DENOBLE, P. J. The healthy diver: A cross-sectional survey to evaluate the health status of recreational scuba diver members of Divers Alert Network (DAN). PLOS ONE, v. 13, n. 3, p. e0194380, 2018. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0194380.

SELYE, H. Confusion and controversy in the stress field. Journal of Human Stress, v. 1, n. 2, p. 37–44, 1975. DOI: 10.1080/0097840X.1975.9940406.

SMITH, N. Scuba diving: how high the risk? Journal of Insurance Medicine, v. 27, n. 1, p. 15–24, 1995. Disponível em: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10158133. Accessed on: January 12, 2025.

STRAUSS, M. B.; AKSENOV, I. V. Diving Science. Champaign: Human Kinetics, 2004.

Author

Luiz Cláudio da Silva Ferreira

CMAS Instructor # M3/10/00001

PADI Tec TRIMIX/DSAT Instructor # 297219

DAN Instructor #14249

#007.615.457-27