Por Luiz Cláudio S Ferreira (DecoStop Nr 62)

This story began after the conclusion of the “Andrea Dória Project 2016 – Brazilians in the Everest of Diving”, whose 2-year preparation and execution trajectory had been reported, since its inception, in issues 44, 46 and 49 of DECO STOP magazine.

After the success of the mission in Dória and surfing a wave of enthusiasm for technical diving in extreme conditions, it was natural to seek an equivalent objective. It was not long before, and quite unexpectedly, when planning a return to Sharm El Sheikh (Egypt) for a few days of recreational diving, I discovered one of the most emblematic and challenging deep-sea diving spots in the world: the Blue Hole of Dahab.

That Blue Hole would be the justification for resuming technical training and ensuring the safe exploration of a beautiful underwater trench, also known as the “Divers’ Graveyard”.

Photo: Petar Milošević

Dahab: A Jewel in the Sinai

Dahab is a charming coastal town located on Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula and is a world-famous destination for snorkelers and divers of all types: free, recreational and technical. Its origins date back to ancient civilizations, with traces of Bedouin camps and trade routes that have crisscrossed the region for centuries.

The town is located approximately 80 kilometers north of Sharm El Sheikh and can be reached by air, with frequent flights from Sharm El Sheikh International Airport, followed by a drive or bus to Dahab. Regardless of the mode of transport chosen, arrival in Dahab is always marked by the warm welcome of the local people and the stunning views of the turquoise waters that surround it.

Dahab’s transformation over the years from a sleepy fishing village to a bustling tourist destination is testament to its original appeal. However, the city’s authentic soul remains intact, with its seaside cafes and markets full of spices, fabrics and local crafts, providing an extraordinary cultural experience.

Photo: Author

The Blue Hole: Wonder and Mystery

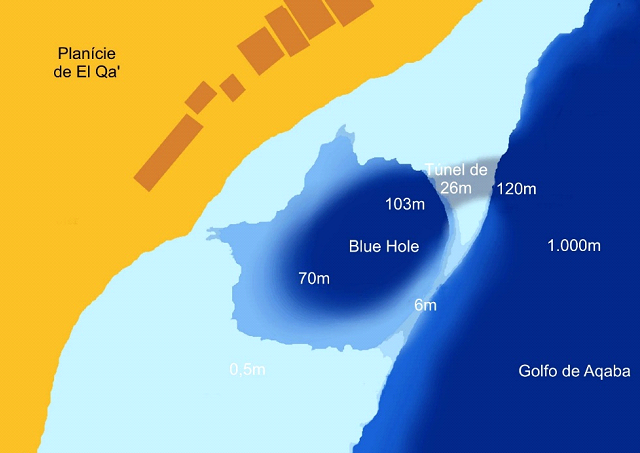

Dahab’s main attraction is undoubtedly the Blue Hole, a natural abyss of unparalleled beauty and mystery, located just a few meters from the rocky shores of the South Sinai desert, at coordinates 28°34’17.9″N 34°32’11.5″E. Geologists believe that this underwater sinkhole was formed thousands of years ago, during the melting of the last ice age.

Dahab’s Blue Hole is a formation measuring about 130 meters in diameter and 120 meters deep, surrounded by a nearly vertical reef wall. Its edge opposite the beach is at a depth of 6 meters, forming a structure called “The Saddle”, which connects it to the open sea on the surface. On the northeast side there is an underwater passage called “The Arch”, which starts at 56 meters and descends to 120 meters, connecting it to the deep sea, in the Gulf of Aqaba, abruptly reaching the 1,000 meter mark.

During the Israeli occupation of the Sinai Peninsula, the Blue Hole gained international notoriety as a diving destination. In 1968, a group of Israeli divers, led by Alex Shell, carried out the first dive with equipment at the site and recorded the underwater arch.

Photo: Author

The site can be visited all year round, but the best time to dive is from June to August. During this time, the weather conditions are most favorable, with water temperatures hovering around 28°C and visibility reaching up to 50 meters.

The unique beauty of Dahab’s Blue Hole is shrouded in a dark aura, as the site has claimed the lives of many divers, with unofficial estimates ranging from 130 to 200 deaths over the years.

History of Fatal Accidents at the Blue Hole

Unfortunately, the Blue Hole has earned a reputation as one of the most dangerous diving sites in the world. The combination of extreme depth, lack of underwater landmarks, the temptation to explore the Arch unprepared and unpredictable current conditions have contributed to numerous incidents, making the site a challenge for even the most experienced divers. Determining the exact number of deaths at the Dahab Blue Hole is also a difficult task, due to the varied nature of information sources and the lack of a centralized official record. Furthermore, information resources are limited to reports from dive operators, news reports, publications, online forums and diving communities. However, estimates suggest that close to 200 divers lost their lives at the Blue Hole, which has earned it the nickname “Divers’ Graveyard”. Many of these deaths are specifically attributed to decompression problems, nitrogen narcosis, oxygen toxicity, lack of gas in the tank, blackouts and human error resulting from the complexity of technical diving at great depths. Several publications have documented the deaths at the Blue Hole, highlighting the dangers of the site. Dennis Kenyon’s book “Shadows Over the Blue Hole” examines fatal accidents and safety lapses, while National Geographic’s “Inside the World’s Deadliest Dive Site” explores the dark history of the challenges faced by divers at the Blue Hole.

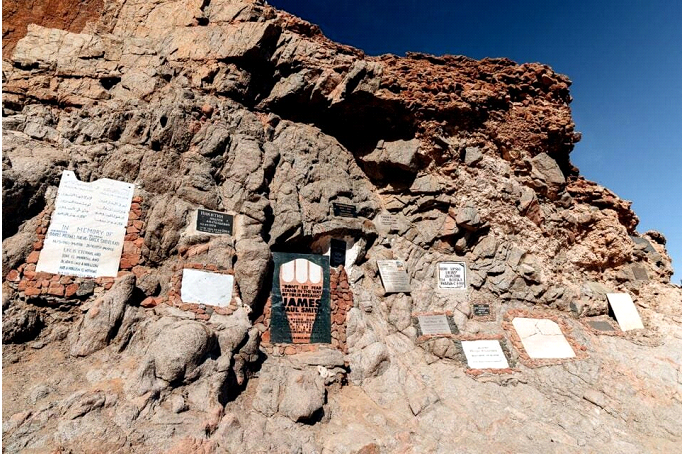

A number of fatalities have become notable for the dramatic circumstances in which they occurred—such as Yuri Lipski (a 23-year-old Russian diving instructor who was found at 375 feet (115 meters) on April 28, 2000, and tragically filmed his own death); Conor O’Regan and Martin Gara (Irishmen, 22 and 23 respectively, considered cautious divers, on November 19, 1997, found at 330 feet (102 meters); Andrei (another Russian, on August 24, 2004, whose body was not found); Karl Marx (an Austrian, on January 10, 2007); Stefan Felder (Swiss, September 23, 2008); Madlen (diving instructor from Sachsenhausen, May 9, 2009); Bethany Rockwell (experienced diver, 2012); Stephen Keenan (Irishman from Dublin, 39 years old, drowned while trying to rescue world record holder freediver Alessia Zechhini, July 22, 2017); Igor Shalo (Russian, technical diver with over 400 deep dives, November 7, 2011, found at 150 meters). In addition to these, many others are recorded through posthumous tributes, inscribed on tombstones and fixed a few meters from the beginning of the Blue Hole.

Photo: Author

There is also a list of missing persons related to the site and it is believed that many bodies have not been recovered from the seabed to this day. According to Tarek Omar, a renowned technical diver who is responsible for most of the rescues of injured divers in the region, there is a tank and a wetsuit resting at 170 meters. According to Alex Heyes, another extremely experienced technical diver who ran the H2O Dive Center in Dahab for many years: “The challenge of the Blue Hole is to the recreational diver what Kilimanjaro is to the hiker”. Alex Hayes died during a technical dive in the Blue Hole in 2011. Interestingly, it is estimated that in the last 27 years, from 1997 to 2024, the majority of fatal accidents have occurred with technical divers and those considered highly trained, many of them diving instructors. And, due to this history, local authorities have been led to impose strict regulations to ensure the safety of divers, such as prohibiting dives by single individuals and requiring proof of experience for dives below 40 meters.

*** THERE IS NO MEDICAL CARE ON SITE AND THE NEAREST HYPERBARIC CHAMBER, BELONGING TO THE DAHAB HYPERBARIC MEDICAL CENTER (DHMC), IS A 30-MINUTE DRIVE AWAY ON A GRAVEL ROAD.

Preparing for the 100-Meter Dive in Dahab

Technical diving with trimix opens the door to exploring greater depths, such as the Blue Hole, but it also presents significant risks that are not dependent on the environment being explored and that cannot be underestimated. In order to eliminate as much as possible the factors that could lead to stress, the need for improvisation, the failure of the project or the physical safety itself, it was necessary to undertake a continuous work plan in the cognitive sphere (in-depth studies on the Blue Hole parameters and main documented difficulties, dive profile, gas theory, decompression techniques, emergency and contingency practices, effects of stress on decision-making and others), technical (choosing and preparing appropriate equipment) and psychomotor (establishing a routine of physical exercises, dives in similar conditions and simulations of contingency measures), which culminated in a final training dive, at a depth of 100 meters, on the walls of Fernando de Noronha, with the support of Fernando from SeaParadise.

Photo: Author

The Target Dive

Once in Dahab, for the execution of the main objective, I was joined by the distinguished TDI Technical Diving Instructor, Andreas Sues, known for his significant contributions to the science of deep diving. With extensive experience in technical and trimix diving, Suess is a respected figure in the international diving community, particularly in relation to the development of new decompression algorithms, which are now widely used in the diving community.

Suess has participated in scientific studies that analyzed the effects of decompression under different conditions, including the analysis of data from real dives and laboratory simulations to better understand the risks and best practices for decompression. He is a co-author of the study “Advancements in Decompression Algorithms for Technical Diving,” which was published in the *Journal of Diving and Hyperbaric Medicine*.

The first stage of the work included reviewing the target dive profile, identifying gases and planning redundancies. The decompression model chosen was the ZHL 16-C + GF (Gradient Factors), which incorporates modern data from clinical studies and brings updates based on recent research, aimed at optimizing the accuracy of decompression profiles. The parameters used were: PPO2 (Partial Pressure of Oxygen) of 1.4 above 28 meters / 1.5 from 28 to 45 meters / 1.6 from 45 to 99 meters; RMV (Respiratory Minute Volume) Botton 20 l/min and Deco 20 l/min; minimum GF of 35 and maximum of 80; descent rate of 10 m/min to 10 m and 18 m/min from 10 to 100 m; ascent rate of 10 m/min to 6 m and -1 m/min to the surface.

Photo: Author

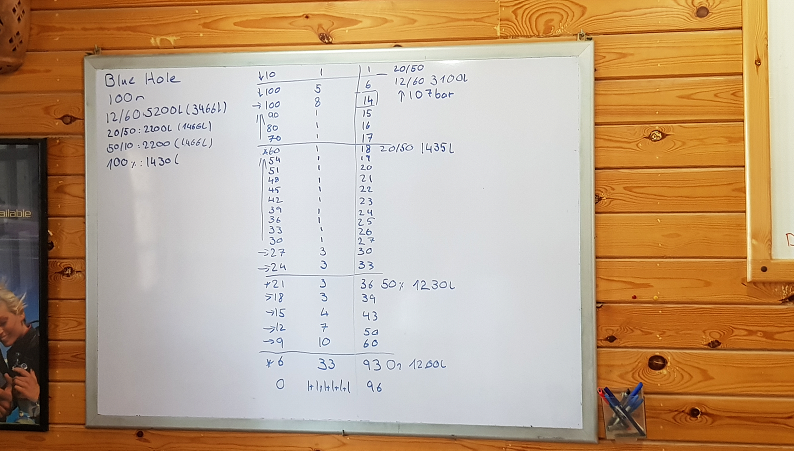

The final gas configuration was 01 (one) double S80 with Tx 12/50 (background gas), 01 (one) stage S80 with Tx 12/60 (travel and decompression gas), 01 (one) stage S80 with Tx 50/10 (travel and decompression gas), 01 (one) stage S80 with 100% O2 (accelerated decompression). And the complete immersion and decompression scheme was: Tx 20/50 (↓10m/1′), Tx 12/60 (↓100m/5′, →100m/8′, ↑90m/1′, ↑80m/1′, ↑70m/1′), Tx 20/50 (↔60m/1′, ↑54m/1′, ↑51m/1′, ↑48m/1′, ↑45m/1′, ↑42m/1′, ↑39m/1 ‘, ↑36m/1′, ↑33m/1′, ↑30m/1′, ↔27m/3′, ↔24m/3′), Tx 50/10 (↔21m/3′, ↔18m/3′, ↔15m/4′, ↔12m/7′, ↔9m/10′) and O2 100% (6m/33’). The support of a safety diver at 22 meters, Trimix TDI Instructor Kerstin Olbrich, was also considered.

The second stage consisted of two training dives, at recreational depths, for the final adjustment of individual equipment, gas exchange testing and training in contingency measures.

The third stage consisted of refilling the cylinders, checking the partial pressures of the gases, identifying each cylinder, pre-assembling the equipment and, finally, the necessary rest for the event the following day.

Photo: Author

The main dive would already be an incomparable experience, but it was especially brightened by a beautiful, sunny morning, beautifully framed between the Red Sea and the El Qa’ plain.

We immediately got equipped and advanced along a submerged plateau, about half a meter deep, to the edge of the abyss where the dive would actually begin. At that moment, the sunlight was already penetrating the crystal-clear waters, creating an interesting kaleidoscope effect of blue and green colors.

We began the descent and, as we progressed, the water temperature remained comfortably at around 27°C and visibility still extended in the underwater environment to considerable depths. The feeling of tranquility and peace was almost immediate.

Going through the first 30 meters, it was possible to feel the lightness of the nitrogen decreasing and the helium of the trimix taking over its role, providing the mental clarity that is crucial for deep diving. The walls of the Blue Hole, covered in coral and inhabited by a diversity of marine life, with countless clownfish, anemones and huge blue tridacnas, seemed to tell a long and ancient story.

At 50 meters, the sunlight began to fade, but visibility was still excellent, revealing the impressive contours of the Blue Hole. At 80 meters, we already had the best view of the famous “arch” and, through it, the vast darkness of the open sea. The excitement increased, as did the attention to the instruments and communication with the partner, to reinforce the team spirit.

Finally, upon reaching 103 meters, the view was surreal, with a deep blue twilight all around, which gave an almost ethereal feeling of gratitude and satisfaction for having reached this iconic location.

Photo: Author

Photo: Author

At 14 minutes into the dive, we began our return to the surface, following the previously planned decompression profiles, almost wishing that the decompression stops would be extended to prolong the experience as much as possible.

We found Kerstin at 22 meters and continued climbing until we finally broke the surface and were greeted once again by the warmth of that beautiful day, reinforcing our gratitude for the opportunity to explore one of the most challenging and beautiful dive sites in the world.

We ended the mission with a delicious Bedouin tea, made with local herbs and mint, served right in front of the entrance to the Blue Hole, in one of the local restaurants.

The Dahab Blue Hole combines stunning beauty with extreme challenges and will continue to attract technical divers looking for an epic experience. However, it is crucial that the site is explored with respect and adequate preparation, so that the happy ending can pave the way for an unforgettable experience, full of adventure and personal fulfillment.

The visit to the Dahab Blue Hole was interspersed with a tourist trip and several other recreational dives, all fondly remembered, but here is a recognition of the support of friends whose technical collaboration was essential during the training phase: Fernando (Sea Paradise), Stavros (Alliance IDC) and Miltinho (Alliance IDC).

Divers, ready… WATER!!!

References:

– Bennett, P. B., & Elliott, D. H. (2015). The Physiology and Medicine of Diving. 5ª ed. Londres: Saunders Ltd.

– Edmonds, C., Lowry, C., Pennefather, J., & Walker, R. (2015). Diving and Subaquatic Medicine. 5ª ed. Londres: CRC Press.

– Powell, M. (2008). Deco for Divers: A Diver’s Guide to Decompression Theory and Physiology. Dorset: Aquapress.

– Mitchell, S. J. (2018). “The physiology of deep diving: what’s known, what’s not, and what we would like to know.” Diving and Hyperbaric Medicine, 48(4), 225-235.

– Divers Alert Network (DAN) (2019). DAN Annual Diving Report. Durham, NC: Divers Alert Network.

Author

Luiz Cláudio da Silva Ferreira

CMAS Instructor # M3/10/00001

PADI Tec TRIMIX/DSAT Instructor # 297219

DAN Instructor #14249

#007.615.457-27